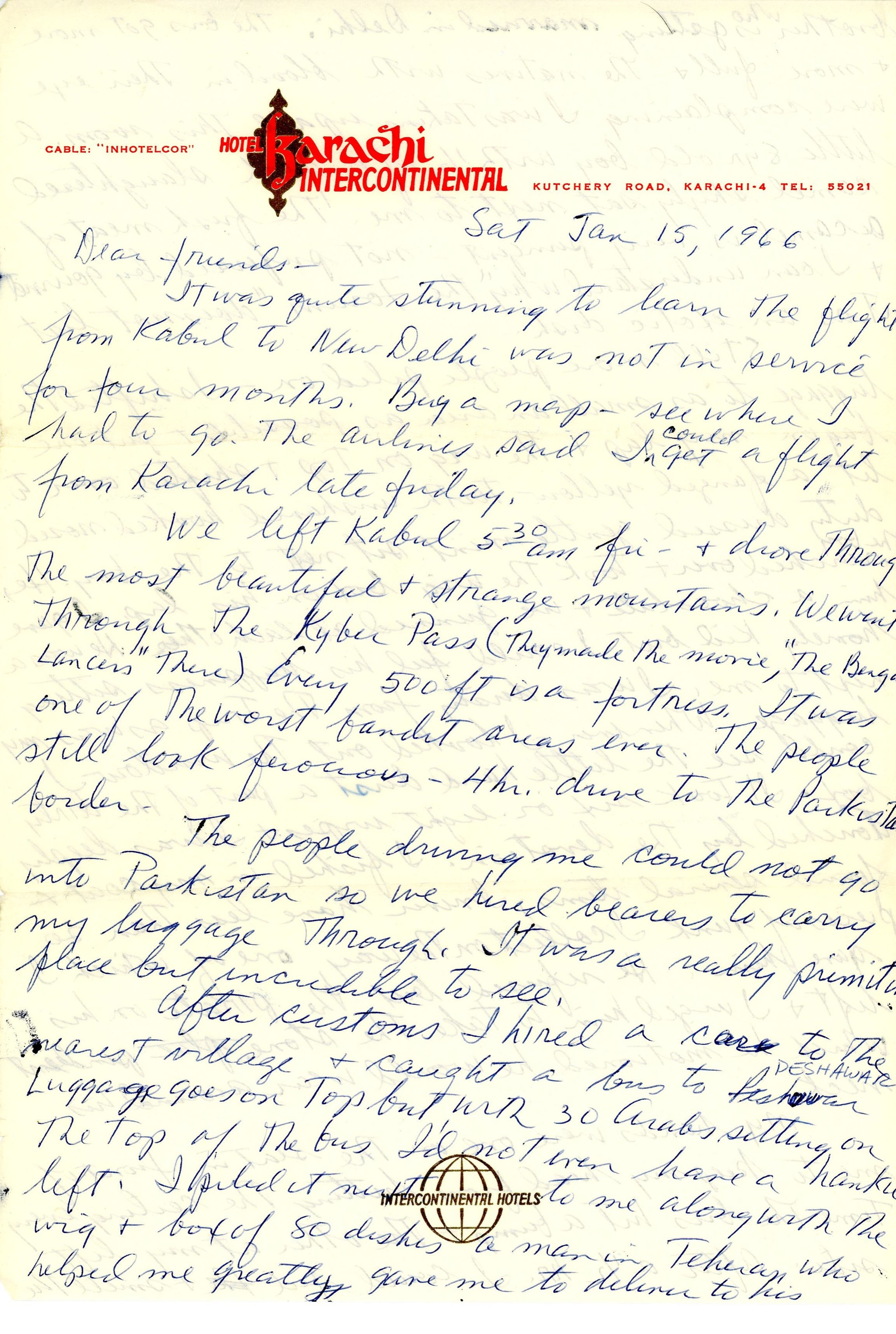

A Letter from Karachi

January 15, 1966

Dear Friends,

It was quite stunning to learn the flight from Kabul to New Delhi was not in service for four months. Buy a map—see where I had to go. The airlines said I could get a flight from Karachi late Friday.

We left Kabul 5:30 am Friday and drove through the most beautiful and strange mountains. We went through the Khyber Pass (they made the movie “The Bengal Lancers” there). Every 500 feet is a fortress. It was one of the worst bandit areas ever. The people still look ferocious—4 hour drive to the Pakistan border.

The people driving me could not go into Pakistan so we hired bearers to carry my luggage through. It was a really primitive place but incredible to see.

After customs I hired a car to the nearest village and caught a bus to Peshawar. Luggage goes on top but with 30 Arabs sitting on top of the bus, I’d not even have a hankie left. I piled it next to me along with the wig and box of 80 dishes a man in Teheran who helped me greatly gave me to deliver to his brother who is getting married in Delhi. The bus got more and more full, and the natives with blood in their eyes were complaining I was taking up all this room. A little 8 year old boy with half of a fresh slaughtered camel shyly sat next to me. The fresh meat of a camel is very pungent—not preferred by gourmets and I can understand why “the Forum” does not list it as an exotic dish.

Still more people piled on—I shifted the luggage to as small an area as possible and put one bag on my lap and the wig on top and shifted over to let a fanged yellow tooth unshaved hook nosed dirty dressed gentlemen sit next to the boy. He, the boy, reached over and took the wig box on his lap. I gave him a chocolate and we grinned at each other. He was a homely kid but I could feel his happiness sitting next to me. I was dusty from the trip as was my luggage. Whenever I looked out the window, I could see the little hand dust a part of the dirty box. It took six or eight wipes, and I was deeply touched by the devotion. I fished in my coat and found several items, I never have less than 20 pieces of junk I collect on the way, one of which I gave him. He refused but the pirate on his left and I urged him to take the stone pendant which he motioned he would wear around his neck.

My hands were one on the seat in front of me to keep my head from hitting the ceiling every time the bus hit a bump and the other at my left side. After half an hour, I could feel and smell the little hand on my left. It was crawling close to mine and I reached out and put a finger on his camel bloody paw. He grabbed it and held tight and all the next 3 ½ hours we were joined. An occasional smile but not much outer recognition.

When we reached the end of the Khyber Pass, a blustering man got on and began talking to me about the wonders of the area. He said I was lucky I met him on the bus as he was in a hurry to reach Peshawar. If I had met him before he said I would have had to spend 2 days seeing the wonders of the area, and I was lucky as his brother was the Chief of the Tribe and so I could go anywhere. I’m sure he had a list of rates which were for arbitration. I swore I would return soon with many friends and avail myself of his hospitality. He raved on as I paid my fare 3 times what it should have been but it included the boys.

Kabul, 1966.

The mud walls surrounding the mud houses were 20 feet high and went about 200 to 400 feet on each side. Turrets another 15 feet or more were on the corners. Not inviting with holes for rifles every 10 feet. The dust-covered people squatting and sitting looked like a partially cleaned mosaic against the background of original dirt. It became evident as we bounced along that time was running out as the plane from Peshawar to Karachi was to leave at 1:30 pm and at 1:20 pm we passed ¼ mile from the airport and the Chief’s brother said he would fix everything. Finally we reached the bus terminal and the boy helped me unload my baggage. Drivers of horse drawn carts tried to grab my baggage when a fellow passenger jumped out of a cart drawn by a motorcycle. He had gotten this for me and piled my things in, gave the driver instructions, and wished me luck in English. The boy and the Chief’s brother waved me off.

Put-putting along we reached the airport and not a sign of a plane. It was 1:40 pm and not even a person at the airport. I asked one of the uniformed men and he said the 1:30 plane for Karachi left at 1:20. I prefer missing by a mile not an inch, so I dragged my luggage and a porter helped me into the lounge.

The airline men were very considerate and told there was a 6:20 plane to Rawalpindi connecting with a Karachi flight. They ordered tea and cake, and I stepped out of the lounge onto a grass and tree yard and felt I was meant to relax and enjoy the beautiful sunny day. A boy of 10 with his loose cotton robe, one end between his teeth, was contemplating me from the distance. He circled me and stood 20 feet off for 10 minutes while I was having my tea. He approached and opened the wood box he had supported by a wide leather strap on his shoulder. It contained shoe polish and brushes. “Shine?” he asked. “How much?” said I. “One Rupee.” I thought it over for half a minute and brilliantly said “One half Rupee.” “Okay.” After the shine, he had only 15% of the change he should have given back. I never in my life remember a shoeshine boy in the East who had the correct change. He won his deal and I had a good shine. The sun beat down and shed the gratitude I also felt from within myself. To have this adventure was far more wonderful than any inconvenience, and I was happy I had reached a place where the petty values of life were disappearing.

The tea tray was removed by a wonderful old Pakistani who treated me as if I were an Army general and he a Sargent—obviously training from British India—a quality of humanity, not slavery. So often good taste and servitude towards others is misconstrued as weak. Each man is a servant or he is a fool. If one does not serve his own life and that which he is given, he only destroys it with his Ego. The old man added much to the warm sun on me and the grass and trees. He too was the best of nature and set my mood for relaxing.

Two of the personnel from the airlines drifted out and we chatted. They asked my business and I said I dealt in novelties—I think we all deal in such—they asked where and for how long I was stopping. As each place was only a few days and Bombay two and a half weeks, they asked why. I explained I was to go into an ashram for 2 weeks some 50 miles from Bombay. We began to talk about religion and they asked why the Hindus worshipped idols with three heads or no arms or elephants etc. I explained that these things were only symbols of spiritual forces as they occurred at different levels. I mentioned all these powers were similar. If a man looked at an idol or other representative forms it does not mean anything. It is more important that he develop his own inner powers. They asked when I began my study—I said at 6 to 8 years I could read palms and do some psychic work.

Without much ado, the younger man held out his hand and asked would I please read it for him. I found a very superficial set of lines with no maturity. The man was a boy—a nice boy if you were nice—completely reacting to whatever the mood he was in presented.

The other man had a wonderful depth. I felt enormous potential quality which was only developed on a minor scale. His mind would not permit the opening of these deeper aspects he had. I tried to explain that the mind and emotions are like a man and wife. They cannot fight and have a happy marriage. He had no harmony within these two parts of himself. Even more important is the spirit of man, which is the father of the mind and emotions. When the children—the mind and emotions—listen to their father the spirit then there is a true family and a good home grows. He tried to listen, but his reason kept bringing words to his mouth and he talked and closed the depth within himself.

Several more men drifted over. The quality of all of them was quite wonderful. I felt I should fill out the P.I.A. form on the plane and say that their selection of men in Peshawar was quite wonderful to sit with and talk. The genuine wish to be gracious and then hospitable was very noticeable as they asked if I would care to eat or drink. They were all fasting as it was the Holy Month of Ramadan. All Muslims fast from sunup to sundown.

One man sat quietly and the wisdom and simpatico I felt within him as he would nod his head as I spoke. It was a deep effort for me and was bringing me up to my best. I have learned never to give anyone less. Whatever they take is one aspect but the best I can do teaches me and helps me grow.

Peshawar Airport, 1960s.

The flight to Delhi they were trying to arrange finally was set and they issued me a ticket for late Friday or really Saturday morning 2:30 am. It was a Lufthansa flight. A half hour later they said it was no longer running and gave me a refund.

About this time passengers began to arrive and I sat in the lounge as the sun was setting and it was becoming cold. I noticed a young man of 30 had been sitting nearby when I was talking to the P.I.A. man. When I entered the lounge he was just being served tea. He asked if I would care for some. I thanked him as I had just had my second tea. We talked and he was leaving for Rawalpindi. He asked where I had come from and had I seen Peshawar. When I said no, he told me of the wonderful sights and the ivory and things which Peshawar was famous for.

He was very shy and the deep light within his eyes shone with the goodness and friendship he was sharing. He asked if I was stopping at Rawalpindi. I said no. He said that he knows I must have much important things to do but I could be his guest if I cared to see the wonderful markets of Rawalpindi and I would be well taken care of. This great hospitality and the ability to love even a stranger is the greatest attraction I found in India, Pakistan and much of the near and Far East. To be open with any decent human being opens such hospitality and depth that I always feel reassured on these trips. I explained that I was to try for a plane that night.

When we reached the plane we sat several rows apart but as I filed out I found my new friend helping with my luggage. We stopped at the foot of the plane and he gave me his card, and we exchanged names and addresses. He again said I would be a welcome guest and I must try to come back and see this part of his country. We shook hands and I hugged him, and as we entered separate doors at the airport, me as a Transit, and he to return home, we waved goodbye.